Thinking of Prose—Clarity, Diction, Cadence

A multi-post series examining three great elements via Scott Thomas's Kill Creek.

At its most basic, we have said that prose is the words you chose and how you put them together. We also said that prose has three levels. The first is the simple communication of what. This type of prose is clear and readable, doing a decent job of moving what is in the writer’s head into the reader’s head. The second level features some degree of “nuance and flow.” That is, the writer is occupied not only with what is being communicated, but also with how—starting to ask and answer the question of not just what to convey but how to do so. Specific word choice and use of devices all come into play here. The third level is prose “seduction.” Seduction involves cementing your intent: why are you making the word choices and grammar choices you are in each sentence? Why is this the most effective way of communicating with readers?

We want to offer you a fresh analytical framework from which to think about prose.

What Makes Great Prose

When we think about the basic question of what makes great prose, three things comes to mind:

Clarity

Cadence and rhythm

Meaningful diction

Just because you write a sentence and know what it means doesn’t mean a reader will understand. Clarity vastly increases the chance that what you intend to write will manifest in a reader’s head. Many of the ideas we will discuss in our eventual grammar deep dive, such as word order (most commonly subject, verb, object in English), the types of sentences (created by combining independent and dependent clauses), and the proper ways of joining clauses will help with this. Once you can communicate clearly, sentence by sentence, you can also consider how to be artful.

That is where we reach cadence and rhythm. By those words, we mean exactly what you might think. How does your writing flow? Does it carry readers along with the dynamism of word choice (another element we list above) and sentence structure, or is it stiff and formulaic? Is it clear but boring, or does it become more than the sum of its parts? The same way that a gushing stream is more interesting to watch than a flat river, so writing that incorporates cadence and rhythm is more engaging that a monotonous string of repetitive sentences. At the same time, it takes more skill to navigate the stream than the river. Don’t jump in headlong, or you and your reader may be swept away. Swim in the calm water first. Then try something with more verve and variation.

Both cadence and rhythm rely on variation. By that, we don’t mean informational variation. Of course each sentence should communicate something new or different. Rather, we mean structural variation. As in, your sentences look different and are put together differently. And not just variation for variation’s sake. You should align your sentence structure to your storytelling. Use the tools of variation to effectuate the things you’re saying. What are those tools? They include things like (1) repetition, (2) word order, (3) device, (4) sentence tension, and (5) sentence placement.

In all of this, we will begin to touch on the important matter of “word choice” or “meaningful diction.” You writing should be clear. Your writing should have cadence and rhythm. And in that environment of clarity and flow, you should look to make interesting word choices, where appropriate, that command our attention. Importantly, meaningful diction does not necessarily mean “fancy words,” just the right words.

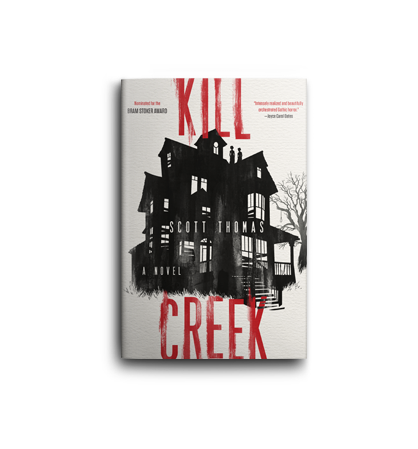

We’ll examine each of these three elements—clarity, cadence and rhythm, and meaningful diction—in the opening of Scott Thomas’s Kill Creek. If you haven’t read Kill Creek, pick up a copy today and get ready for Scott’s third book this coming April 31st.

Kill Creek

This passage will be familiar to you from the last post. It is the first few paragraph from Scott Thomas’s Kill Creek:

NO HOUSE IS BORN BAD. Most are thought of fondly, even lovingly. In the beginning, the house on Kill Creek was no exception.

The house was made from nothing more fantastic than wood and nails, mortar and stone. It was not built on unholy ground. It was not home to a witch or a warlock. In 1859, a solitary man constructed it with his own two hands and the occasional help from friends in the nearby settlement of Lawrence, Kansas. For a few good years, the many rooms within the grand house were filled with a passionate love, albeit one shared in secret, a whisper between two hearts.

But as with most places rumored to be haunted, a tragedy befell the house on Kill Creek. The man who built it was murdered, mere feet from the woman he loved. His outstretched hands attempted to span that mockingly short distance between them, to touch her dark skin, to caress her hair; his mind insisting that if he could just hold her, they would both be saved, that if he could just wish hard enough, they could still be together.

They were not saved. His love’s body was taken from beside his own and hung from the only tree in the front yard, a gnarled beech. She was already dead, and yet they strung her up in one final insult. The bodies became as cool as the steamy August night would allow, the silence of the house and grounds lying over them like a death shroud. They would remain undisturbed for several weeks, forgotten as the town of Lawrence endured its own tragedy. As dusk fell, the horizon to the southwest flickered with the orange glow of flame. Lawrence was burning.

A house stained by spilled blood cannot escape the harsh sentence passed by rumor. The townspeople, traveling the quiet dirt path to Kansas City, began to speak of the house as if it were alive. How badly they felt for the poor, sad place, orphaned as so many children had been during the bloody border battles preceding the Civil War. It was impossible to say what happened within that empty house on long, dark winter nights, when the wind cut through the barren forest to rattle its windowpanes. There was just something about the place that inspired travelers to quicken their pace as they passed Kill Creek Road.

We discussed this at a high level in the last post. In the next post, we’ll dig in and start analyzing this introduction in terms of clarity, cadence, and diction.

—The Inkshares Team